To engage with this performance is as difficult as the emotions and thoughts it agitates. For some of the audience, it might have also stirred up memories. This one hour and a half play felt like a walk in the confusing and overwhelming backstreets of Beirut, where Hanane and Randa led the way and made sure we don’t get lost.

It is strange to start with the end. Yet, the performance might be purposely or unintentionally leading to that specific moment, the grand finale. The finale encapsulated the whole performance. It was its crowning, its zenith. In itself, this was a moment of power and vulnerability. Two women, two actresses leaning on each other in an intimate hug on a stage they unquestionably just conquered and owned. They don’t have to prove that fact to anyone.

On the other hand, the opening scene was the defining moment. From the start, Hanane and Randa positioned themselves as women actresses in a male dominated profession and a patriarchal society. They elaborated, using a fiery dialogue, about the director, the writer and the producer who ‘own’ the work versus the actresses who receive a ‘yaa’tikeh el afyeh’ (pat on the back). Each, in her own way, unapologetically presented herself as a woman with a different story and a different living experience. They made us aware that theirs and the others’ stories that will unfold are stories narrated by women who are ‘icons’ of their own tales.

The dialogue and the performance were constructed to go back and forth. An ebb and flow between intensity and lightness, during which Hanane and Randa were untangling with patience and care the history (ies) of the theater, of a city, a country and a region, and uncovering the stories of the people who lived there and made those histories mainly their own. Smoothly, they went over the religious, political, cultural, economic and social threads, laying them bare in front of us, playing with them, dancing with them, laughing at them. Eventually, they handed them back to us, untangled and knot-free. Like many others in the audience, I left the play with my own share of threads. The ones I could identify. I thought that untangled and knot-free threads are easy to handle. Yet, on the contrary, they are heavy and tripping. Etel Adnan, in her book Master of the Eclipse, asks, “What is he if not a mass of confusion always searching for the very thing that he will refuse to grasp whenever the grasping becomes possible?”. She refers to a man in this quote. I wonder if Hanane, Randa and Chrystel did exactly that. They made it easier to grasp this notion, and it was up to us to decide whether to refuse or embrace what we received.

In a country where there is little to no collective memory, as well as little to no efforts to build it, Hanane, Randa and Chrytel worked on building a collective memory of the theater, particularly in Lebanon during the civil war. They portrayed eloquently the different faces a theater can embody and its relationship with the city[1]. In a divided city, the theater naturally took on divided identities. What if the city was united and one? What would be the identity of the Lebanese theater then? Hanane and Randa asked themselves that. Yet, the question I left with was ‘What is Theater?’. For Hanane, it is in itself a political act; it is the space for many causes to come to life. With the Hakawati Group, the main cause was to fight for diversity. Theater for her is the ‘We’. For Randa, the theater in itself is the cause. It is the place to escape the prison we live in, or we are forced to live in, and thus, is worth fighting for. Theater for her is the ‘I’. Hanane wanted to change the world; Randa wanted to find herself.

Both actresses presented themselves as they are: true and genuine, with their similarities and their differences. It’s like they were saying to a diverse and mixed audience that diversity and difference are okay. They can co-exist on the same stage. At a professional level, Hanane and Randa succeeded in establishing an interesting power dynamic. The veteran actresses could not be more fit to stand in front of each other. Each one of them took her own unique space without shadowing the other. This leads me to the ‘we’ mentioned numerous times in the performance. The ‘we’ is clear in this work; Chrystele’s writing and directing and Hanane and Randa’s performance could not be discussed as separate entities. The three women managed to create a complete and solid body of the many and diverse pieces and voices they had. The ‘we’ is brought together by ‘Jawã[2]’; one of the final stages on the love spectrum in Arabic Literature. Much like the many names they referred to in the play, they have a burning love to the theater that almost causes the body to ache. Randa quotes Remon Jbarra saying ‘theater is born from aches”.

To ease the weight of raw and bare truths, Hanane, Randa and Chrystel offered a small dose of hope. The title in itself, in French/English or Arabic, opens a door to the future. Hanane voiced her dreams of a theater that fits a country and a country that fits a theater. Randa voiced her dream to have an open theater above the ground. They left it to us to interpret the performance and perhaps predict (help shape) the future. Perhaps this miracle play that became a reality amidst a pandemic, economic downfall and political failure would continue a legacy of an unyielding Lebanese theater.

Article edited by Hajar Assaad

[1] To read more about the relation between the theater and Beirut, see Hanane Haj Ali’s book Teatre Beirut, (2010).

[2] http://www.qfi.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/QFI_Infographic_Love_final_web-1.pdf

ARTICLES SIMILAIRES

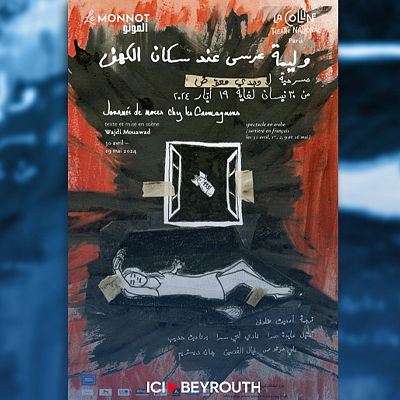

"Journée de noces chez les Cromagnons", le cri originel de Wajdi Mouawad

04/04/2024

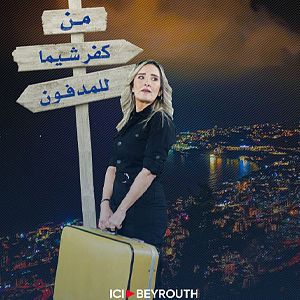

L’époustouflant cheminement de Nathalie Naoum de Kfarchima à Madfoun

21/03/2024

Désopilant « Mono Pause » de Betty Taoutel au théâtre Tournesol

Gisèle Kayata Eid

18/03/2024

Sawsan Chawraba défie la morphine

Gisèle Kayata Eid

18/02/2024

YAHYA JABER l’incontournable conteur

Maya Trad

13/02/2024

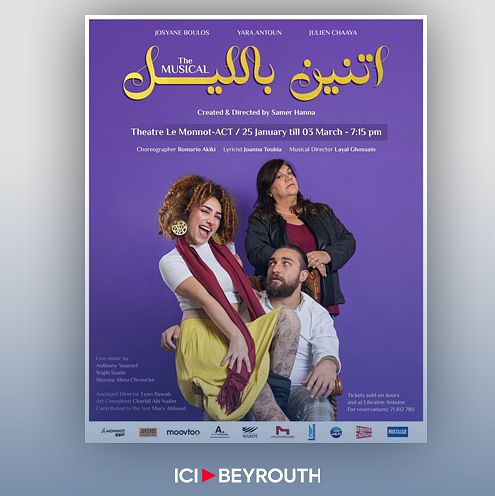

"Tnein Bel Lel": une soirée de rire sans entraves

08/02/2024

Redouane Bougheraba au Liban

29/01/2024

Nada Kano : ‘Dust’ au Théâtre al-Madina

Maya Trad

26/01/2024

« Ennemi du peuple » : Les mots, instrument de pouvoir

Nelly Helou

21/11/2023

Par une nuit de pleine lune : Une heure de détente

Nelly Helou

16/11/2023